Valresultatet i Tyskland spådde fortsatt splittring i landets socialdemokratiska parti. Månaderna efter har dock visat på motsatsen, skriver Die Berliner Replubliks redaktör Tobias Dürr.

”These are the days of miracle and wonder” sings Paul Simon in the song ”The boy in the bubble”. And the German coalition between Sigmar Gabriel’s SPD and Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU is a kind of miracle.

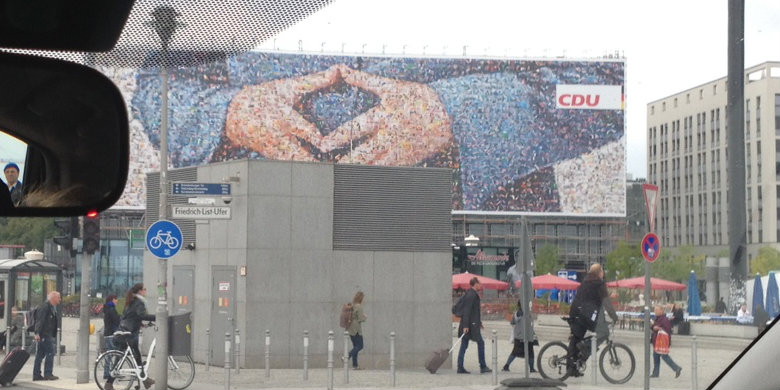

To understand why, we need to return to the 22nd of September last year. It is 6 o’clock in the evening, polls are closing, the results are coming in. The SPD receives less than 26 percent – only slightly better than in 2009 when the party polled a disastrous 23 percent. It is a very, very poor result, especially when compared to the Christian Democrats’ spectacular 42 percent.

For a brief time during election night it even looked as if Merkel had achieved an absolute majority of seats in the Bundestag.

SPD’s election campaign had been very poorly planned and executed. Peer Steinbrück was a knowledgeable but accident-prone candidate. However, “Problem-Peer” was by far not the only problem. There was little coordination of the election campaign, and it lacked a strategic centre.

Instead, different sub-centres of power within the party spent much time blaming each other for all the bad performances during the campaign. Only some weeks before the election date there were rumours of a possible internal coup going around.

In other words: The by far likeliest post-election scenario for the SPD was continued disintegration. What did happen over the following four months, however, has been quite the opposite. This miracle is partly the result of pure luck.

The dominance of the CDU/CSU and the poor results of the SPD (25 percent) and the Greens (8 percent) meant that either a ”black-red” coalition or a ”black-green” coalition was possible.

Had the Greens showed some strategic foresight and real will, they could have joined a Merkel government. This would have been disastrous for the SPD. The party would have lost every bit of its remaining confidence, self-respect and perspective. Continuing leadership struggles, ugly infighting and further decline into irrelevance would have been inevitable.

However, all of this did not happen. Having lost almost three percentage points, the Greens were too busy healing their own wounds to grab power.

Instead, the ”miracle” occurred.

Practically from election night onwards, the SPD’s party leader Sigmar Gabriel did everything right. With his party members being deeply sceptical of a renewed Grand Coalition – mainly because of earlier bad experience – he promised maximum openness.

The negotiations with the CDU/CSU would be a transparent process, everybody in the SPD would be listened to, and all doubts would be taken seriously. Moreover, there would be no coalition unless a majority of party members voted for the coalition agreement negotiated.

There are two major reasons why this patient strategy was successful:

First, with the Greens effectively chickening out, Merkel’s Christian Democrats had no one else to turn in order to form a majority government. This increased the SPD’s leverage, in spite of the poor result at the polls.

Secondly, what increased the SPD’s leverage even further was the membership vote on the coalition agreement that Sigmar Gabriel had promised his party. With the decisive verdict from the rank and file looming ahead, Gabriel could tell Merkel that this or that among the Social Democratic pet projects (pension reform, minimum wage) most definitely had to be included in the agreement. Otherwise the members of his party would tell him to walk away from the deal.

As a result, the coalition agreement looked pretty Social Democratic indeed. Party members were happy – almost 80 percent of them participated in the referendum, and almost 80 percent of these voted in favour. The agreement was duly signed by the new coalition partners, and everybody went on their Christmas holidays.

Now, well over a month into the new government’s term, the SPD has kept the initiative. Sigmar Gabriel has made an impressive and rapid start as the minister responsible for the strategically important ”Energiewende” – a truly bold experiment. This equation involves running an industrial economy without nuclear energy and with declining amounts fossil fuels as possible – while also keeping electricity prices down. A very tall order, needless to say.

Frank-Walter Steinmeier has made a comeback as Minister for Foreign Affairs, a position he had from 2005 through 2009. Steinmeier is thus replacing Gudio Westerwelle of the liberal FDP, who is considered to have taken Germany off the international map while making a fool of himself in the process. Andrea Nahles has already impressed in the influential role as Minister for Labour and Welfare.

These SPD-ministers have all – so far – been highly visible and energetic in word and deed. Meanwhile, Angela Merkel has hurt her butt in a ski accident. She has largely remained unseen for this reason alone. She has continued her job in her usual sluggish, unimaginative and uncommunicative manner. Her party’s ministers have also seemed largely lost for words: no project, no idea, no energy, no sense of direction anywhere.

For the time being, the SPD is running the show in Berlin. A miraculous turn of event, involving ”days of miracle and wonder” as Paul Simon sings. But it remains to be seen how long this honeymoon can continue.

Tobias Dürr är statsvetare och författare. Han är grundare och styrelseledamot av tankesmedjan Das Progressive Zentrum i Berlin samt redaktör för den politiska tidskriften Die Berliner Republik.

Följ Dagens Arena på Facebook och Twitter, och prenumerera på vårt nyhetsbrev för att ta del av granskande journalistik, nyheter, opinion och fördjupning.