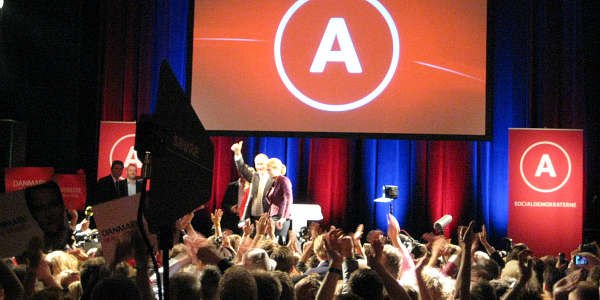

Copenhagen: The cheers were deafening and the tears were flowing at the victory party in Copenhagen on Thursday night when the leader of the Danish Social Democrats, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, finally took the stage. ”We did it”, she announced to the ecstatic crowd around midnight.

Shortly before, Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen had conceded the parliamentary election to Mrs. Thorning-Schmidt, who is now charged with forming a new centre-left government and becoming Denmark’s first female prime minister. The 44-year old former member of the European Parliament lost the elections in 2007 to the now secretary general of NATO, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, but has since grown immensely in stature. Her supporters love her for her modern approach to social democracy and adept communications skills, whilst critics consider her a phony with no real political vision. Her designer outfits and purses make her stand out from most social democrats, earning her the derisive name ”Gucci-Helle” earlier in her career.

The victory party lasted until the small hours of the morning, but prospects of a new government would have inevitably soothed the hangovers of party activists. The Social Democratic leadership, however, might soon find itself nursing headaches of a different kind.

The result was much closer than anyone expected. If around 8000 of the 3.5 million votes cast had shifted from left to right, outgoing prime minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, would have secured a fourth straight win for the conservative coalition – his Liberal Party actually gained one seat in the 179-member parliament. His coalition partner, the Conservative People’s Party, however, was cut in half, losing 10 seats, and the Danish People’s Party lost three seats, marking its first electoral defeat since its formation in 1995.

Meanwhile, Thorning-Schmidt’s Social Democratic Party actually lost one seat while their partners in the pragmatist left-wing Socialist People’s Party, whose leader Villy Søvndal is likely to become foreign minister, were hammered by the voters, losing seven seats. The two other parties in the coalition, the Social Liberal Party and the traditionalist socialist Unity List picked up eight seats each to secure the majority.

So, Thorning-Schmidt becomes prime minister whilst losing seats, with the poorest electoral result since 1903 (24.9%). She leads the second largest party in Denmark behind Mr. Løkke Rasmussen’s Liberal Party (26.7%) and has a noticeably weak coalition behind her.

One might argue that the Social Democrats brought this situation on themselves. The Sass Larsen Doctrine and the economic crisis ensured a campaign fought almost exclusively on economic issues, but even then the party approached the elections like an Italian football team leading 2-0 at half time, preferring to play it safe with their comfortable lead in the polls, letting the other side take the initiative throughout the campaign. And, as such games often go, the opposing team managed to pull one back, and even had a last minute header hit the crossbar.

The government launched a sustained and almost successful campaign to scare voters about the prospect of higher taxes and interest rates, that would result from lax economic policy, and effectively highlighted wedge issues – most notably hijacking numerous voters in Copenhagen’s densely populated suburbs by attacking the left’s proposal to establish a traffic congestion charge.

Yet the safe and simple social democratic message of change (”Denmark needs to move on”) prevailed, however marginally, in the end. The trouble is that the new government is essentially elected without a clear mandate as to how to bring about this change.

Prime Minister Thorning-Schmidt will face two main problems. First of all, her parliamentary majority looks pretty unstable from the outset. The most likely scenario is that she will form a three-party minority government with the Socialist People’s Party and the Social Liberals. She will be able to reach agreements with left-wing Unity List on minor issues, but on major economic reforms she is going to need to broker agreements across the table, and neither former prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who will remain as leader of the opposition, or Danish People’s Party leader Pia Kjaersgaard will be eager to help her. Furthermore, the strength of the Unity List might pressurise her government’s left-wing from reaching too far to the right. The Danish voters have delivered a complex political package to their new prime minister.

Secondly, Thorning-Schmidt will probably be forced to scrap her alternative economic plan, and implement the outgoing government’s pension reforms, raising the retirement age and restricting early retirement options, as the Social Liberals insist on this. If she bucks, her government will fall apart within a week or two. Her dependency on the Social Liberals probably means that she will have to implement some version of the centre-right’s package of austerity and deficit reduction which is dominating mainstream European politics.

As a result of this complex situation, one right-wing commentator ridiculed the incoming government as an ungovernable “Belgian Coalition”, and there is widespread belief that the unstable political environment might provoke an early election in a year or two.

The Social Democrats think they will be able to zig-zag most of their initial proposals through parliament, and hope that Mrs. Thorning-Schmidt’s popularity will increase once she is prime minister, not least because of her potential to make an impact in the international arena when Denmark assumes the EU presidency next year. Thorning-Schmidt has a vast international network, including through her extended family (she is married to Stephen Kinnock, son of former Labour leader Neil Kinnock) and is personal friends with Peter Mandelson, Alastair Campbell and several other figures on the Blairite wing of the UK Labour Party.

Nevertheless, the road ahead for Helle Thorning-Schmidt is rocky at best. It will take an immense amount of political skill to achieve the results on growth and jobs that the voters will expect her and her inexperienced team to deliver.

Whilst there are not many real lessons the European centre-left can take from Helle Thorning-Schmidt’s election campaign, there almost certainly will be a thing or two to pick up from her first year of coalition government. Whether those are lessons of caution or tales of triumph remains to be seen.

Kristian Madsen is editor of Politiken.

Följ Dagens Arena på Facebook och Twitter, och prenumerera på vårt nyhetsbrev för att ta del av granskande journalistik, nyheter, opinion och fördjupning.